Wind Racing

Racing in windy conditions is one of the best tests of a cyclist’s ability that there is. To race strongly in the wind takes a complete cyclist. Physically, it requires a bit of everything: sustaining high power outputs for long periods, explosive efforts to close gaps or follow attacks, endurance to repeat those efforts over and over again until the finish of the race.

But wind racing isn’t just physical, it’s extraordinarily technical too. It requires knowledge of how to react depending on what direction the wind is coming from, how to ride in pacelines and echelons, and how to gain or maintain position in the peloton.

Finally, it’s a real mental challenge, too. Racing in the wind requires an athlete to be ‘switched-on’ at all times, ready for the next corner, crosswind section, or split in the peloton. One moment of relaxation can see you dropped or left with a hard effort to catch back on.

GFNY has plenty of events on the calendar where wind can make the difference in the race. Oceanside events in Cozumel and Mazatlan, races across the plains of Uruguay, and many other GFNY competitions will tax your mental and physical fortitude through hard, windy racing. To be successful at these races, it’s important to understand how to race in the wind.

Racing in the wind can take some experience, and you can’t learn it all simply from reading an article. But knowledge is the first step, so today you’re going to take a big step towards understanding how to race in the wind.

Wind Direction

First, it’s important to understand the differences between headwinds, crosswinds, and tailwinds.

It’s also important you understand that the way wind impacts you on a solo ride isn’t the same way it will impact a peloton during a race.

Finally, we want you to understand the different drafting formations, and which are ideal to use in different scenarios.

Headwinds

Headwinds may be the bane of many cyclists when they’re riding solo, but in windy races, they’re actually the easiest part of the race. Headwinds mean that the riders sitting on the wheels get a huge benefit from drafting, and therefore they have the effect of canceling out attacks. If you’re in the group in a headwind, it’s not wise to attack or to try to split the group.

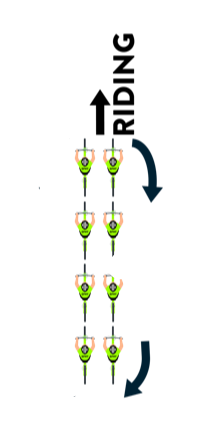

In a rotating paceline, each rider only touches the front of the group for a few seconds before peeling off to one side. This creates a constant flow, with one line being the advancing line and the other the retreating line. Every rider contributes to the pace, but only has to be in the wind for a short time before an extended period of recovery.

In this picture, the left side is the advancing line, while the riders on the right are going backwards before rejoining the advancing line when they arrive to the back.

The best drafting formation to use in headwinds is a rotating paceline. This is because the riders in front are doing much more work than the riders resting on the wheel. Therefore, the best use of your energy is very short, fast pulls at the front before pulling off to let the next rider through. The constantly rotating nature of the double paceline means that the only time you’re in the wind is during the 10 or so seconds you’re on the front. This lets your group conserve energy and maximize speed.

Tailwinds

Tailwinds speed the group up, but they also cancel out some of the effect of the draft. This means tailwinds in a race situation are actually harder than headwinds. They can be a good place to attack and split the group, but it’s still fairly difficult to do so.

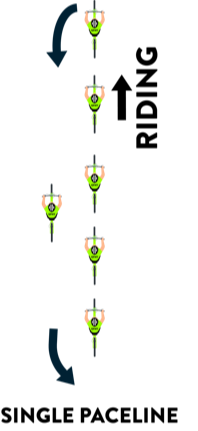

In a single paceline, one rider spends an extended period of time on the front before pulling off and retreating to the back. The principal advantage of a single paceline over a double is that riders can adjust the speed and length of their pulls, letting the stronger riders contribute more.

In a tailwind you can use either a single paceline or a double paceline. Since the difference in effort between those pulling and those sitting on is less than in a headwind, a single paceline can be a viable strategy. This lets stronger riders take longer pulls and keep the speed high. However, in the case of an evenly-matched group or a large one, a double paceline can still be an excellent strategy.

Crosswinds

Ah, crosswinds! Crosswinds are to flat races what climbs are to mountainous races: the decisive points that will split the group and let the strongest show their legs. They also require a lot of technique, and if you haven’t mastered riding in echelons, you will struggle.

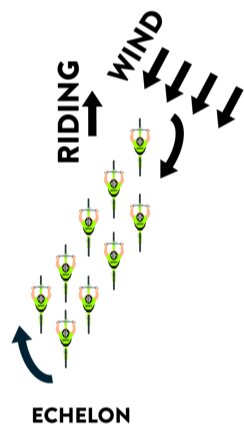

An echelon is a paceline, typically a double paceline, angled to one side to provide riders shelter from crosswinds. The sheltered riders ride both slightly behind and to the side of the rider in front, instead of directly behind him.

An echelon always points the direction of the wind, so in this case the echelon aims to the right to manage a crosswind coming from the right side.

In a normal drafting situation, you’re trying to hide from the wind created by the speed of the group. When the wind comes from the side, the ideal place to sit in the draft actually moves to the side of the rider in front of you, where you have some shelter from the crosswind and some shelter from the wind speed generated by your riding speed.

As you see in the picture above, the echelon is a rotating paceline which is running at an angle. The goal is to shelter from the wind, so if the wind is coming from the right, the leading portion of the echelon should be on the right, and vice versa.

An echelon should almost always be a double-paceline. Without that, the retreating riders waste too much energy. The only exception is if you’re in a very small group, or if not many riders are working. In that case, the echelon can be set up as a single paceline.

Within the category of crosswinds, we have different levels. Cross-headwinds will allow riders who echelon correctly to drop riders not in the echelon, but in the echelon itself riders will be well sheltered. In strong direct crosswinds or cross-tailwinds, things become very difficult, and even using a correct echelon formation, your legs will feel it.

The two riders in yellow and black helmets that we can just barely see are doing a good job of drafting in a crosswind, assuming the wind is coming from the rider’s left: behind but slightly to the right of the lead rider.

Sheltered Areas

Even on windy days, certain features like buildings, forests and hills can provide shelter from the wind. These areas eliminate the possibility of crosswinds and even disrupt the force of head or tailwinds. During windy races, it’s key to look for these points. When you’re suffering in the wind, arriving in a sheltered area can provide the chance to move up or recover. And in a sheltered area before a windy section, it’s the literal calm before the storm: one last chance to prepare for what’s coming.

A thickly wooded section at GFNY Cozumel provides a respite from the wind. Sections like this are the perfect time to eat, drink, recover, and then get positioned for the next windy section.

Positioning

Positioning is absolutely key during windy racing, especially during crosswind sections. If you get stuck behind an echelon, you’re what we call ‘in the gutter’-riding all the way at the edge of the ride, struggling to find some draft that isn’t there. Usually you’ll be dropped, if the pace stays high, and you’ll be forced to find another group to ride with. So before crosswind sections, it’s key to find a position at the front of the group. Use headwind, crosswind, and sheltered sections to find this position before making a turn or emerging from shelter into a crosswind.

In competitive situations, you won’t be the only rider who knows they need to be at the front. You might find much of the group races hard to arrive at the crosswind section at the front, so you’ll need to be on your toes.

In these situations, it’s key to time your effort correctly. If you spend all your gas to move up 5 km before the crosswind, you may find fresher riders come over the top with 500 meters to go. On the other hand, if you get caught all the way at the back, you won’t have enough time to move up last-minute. It’s a good strategy to ride about 20 riders back from the front of the peloton, and then aim to move up into the top 5 or 10 riders just before the crosswind starts.

Lastly: Prepare Mentally and Physically

Windy races are taxing mentally and require your brain to be working all the time. It’s key that you are always thinking of your next move: move up for the crosswind, ride efficiently in the echelon, recover and eat and drink in the headwind or sheltered section. Each section of the course offers a different set of things to focus on.

In your preparation for racing in the wind, do your best to seek out training that challenges you mentally as well as physically. Group rides or training races are key for this; it’s not a good idea to head to a windy race off of purely solo training. Even if where you live doesn’t have much wind, large group rides will challenge your bunch-riding skills and exercise you mentally in similar ways. If you don’t have crosswinds, practice moving around the peloton efficiently and learn to move up just before hills, turns, or hard sections of the ride. These same skills will work in windy races.

Finally, remember that you’ll want to stress your body in training in similar ways to the race. That means plenty of workouts at a high cadence, and long stretches in an aerodynamic position. Group rides are great for this, as are long intervals on flat roads (or on the trainer if you lack extended flat roads where you live). Bump your cadence up 5-10 rpm as this is what you’ll probably feel most comfortable with in the high speeds of the peloton on race day.

Tags: Coaching